The universe that we consider reality is only appearance. All that is perceived by our senses and our mind is maya, illusion. The unchanging Reality is what's behind this appearance. It is Brahman. The Being, that has always been, is innate, and it is the uncreated essence of every living being.

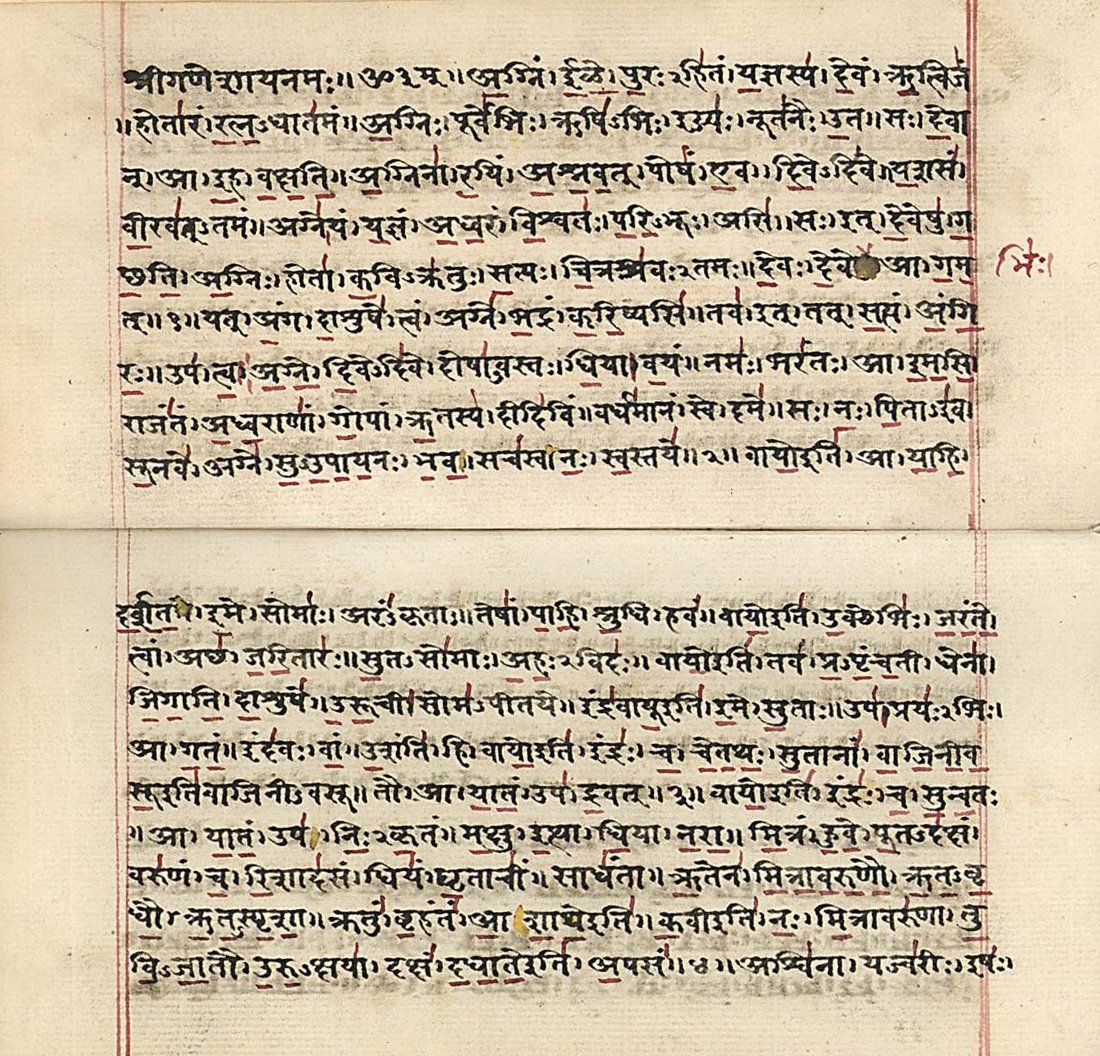

The Brahman that is inside us is the Atman and purpose of human life is precisely the realization of the Atman, that is the experience that Atman and Brahman are the same reality, after which there is nothing that worth knowing. This, in brief, is the essence of Advaita Vedanta, the Vedanta non dual, ie the Vedanta considers that the existing one Reality, the Self and that nothing exists that is other-than-self. This is one of the six darshana or philosophical doctrines of Hinduism that is grounded in the Upanishads, in Brahmasutra and thinking of some philosophers, including Shancaracarya, and which forms the theological basis of Hinduism today too.

The universe that we consider reality is only appearance. All that is perceived by our senses and our mind is maya, illusion. The unchanging Reality is what's behind this appearance. It is Brahman. The Being, that has always been, is innate, and it is the uncreated essence of every living being.

The Brahman that is inside us is the Atman and purpose of human life is precisely the realization of the Atman, that is the experience that Atman and Brahman are the same reality, after which there is nothing that worth knowing. This, in brief, is the essence of Advaita Vedanta, the Vedanta non dual, ie the Vedanta considers that the existing one Reality, the Self and that nothing exists that is other-than-self. This is one of the six darshana or philosophical doctrines of Hinduism that is grounded in the Upanishads, in Brahmasutra and thinking of some philosophers, including Shancaracarya, and which forms the theological basis of Hinduism today too.

To reach the knowledge that Brahman and Atman are the same, we must abandon the '"I" and "mine" that are the biggest obstacles to our realization. "We are what we are - Nisargadatta Maharaj says - but we only know what we are not." We must therefore close the "nine gates" and go beyond perception, beyond concepts, beyond the categories of time and space, name and form.

The universe, what we call reality, is just a personal experience and when a person dies, the body dies and the consciousness of self, but Self doesn't die. "If you want the infinite, abandon the finite - says Maharaj - the finite is the infinite price." That means we must give up everything to get everything. "As long as we think we need things to be happy, we also believe to be unhappy when we lack. In fact we will be free only when we realize that we ourselves are the authors of our slavery, and we stop making things that bind us.

"The Brahman is the end of every desire, every thought and all knowledge. The Brahman is sat-cit-ananda, Being-Consciousness-Bliss Absolute. According to Vedanta this realization cannot be achieved in one lifetime, but it takes many lives, thousands, millions of lives. Atman must rid it of karma, ie the consequences of its actions in previous lives, until you exhaust all residual karma, reincarnation for the last time a human being and attain moksha or mukti, that is the liberation and the interruption of samsar, the cycle of rebirth, to merge the Atman which is inside us with Brahman.

And God, ishvara? God or gods as perceived by men, as every thing that exists in time, in space or in the mind, are destined to die. Religion is generally understood as a step towards self-knowledge. The man has progressed spiritually need something real, a God, an image to turn to, which is devoted. For those who believe in the existence of God, this is Brahman, for those who do not believe, Brahman is an impersonal metaphysical concept, essence and origin of all things and God is just one of many things that live only in the transient our perception.

In reality certain currents of Vedanta - based on selected passages from the Bhagavad Gita too - argue that the way to liberation may also pass through devotion (bakti) or detached action (karmayoga), but the more stringent Vedantists believe that devotion and action are still primitive levels in the path to moksha. Someone, when asked, about the rites and prayers, ceremonies and religion, answers provocatively: "Religion? And what has the religion got to do with God?"

To read:

Chandogya Upanishad

Mundaka Upanishad

Svetasvatara Upanishad

Sankaracharya: Atmabodha, Self- Knowledge

C. Isherwood, The wishing tree

Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj, I am that

Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj,The experience of nothingness

The attainment of Brahman, of the knowledge of the Self, the goal Hindu spiritual path, is called from the Katha Upanishad, "reaching the fearless place" (II, 11). That is to reach "the other side of no fear."

The attainment of Brahman, of the knowledge of the Self, the goal Hindu spiritual path, is called from the Katha Upanishad, "reaching the fearless place" (II, 11). That is to reach "the other side of no fear."