|

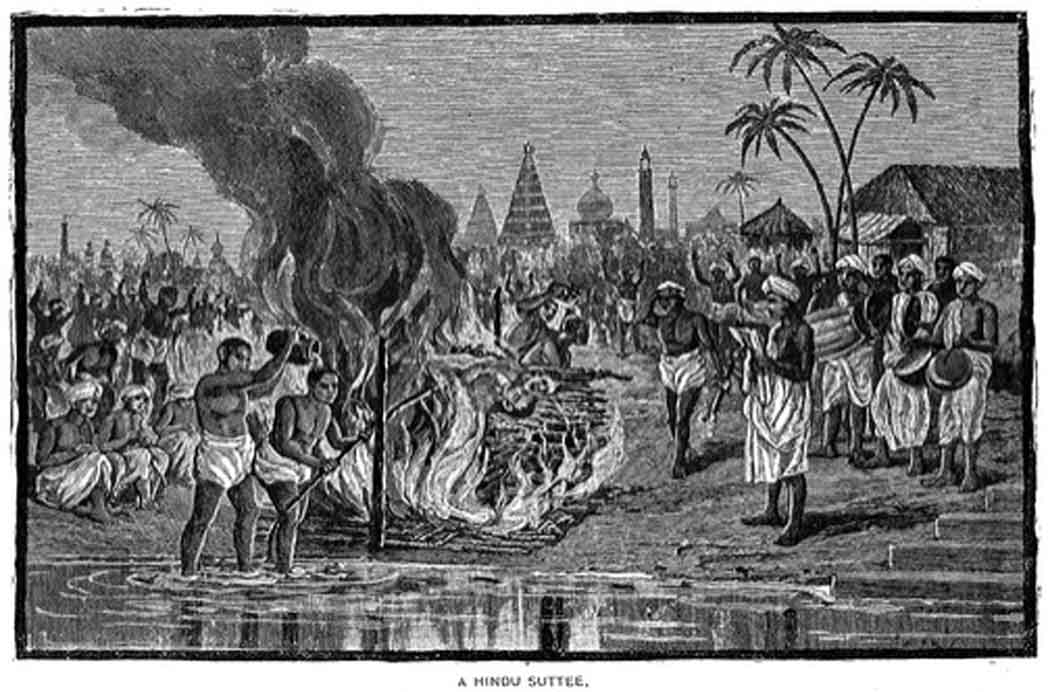

| Cremazione sul Gange a Varanasi |

Nella tradizione induista, il corpo non è altro che l’involucro, l’abito utilizzato dall’atman per incarnarsi e percorrere il lungo tragitto che condurrà questo ‘spirito’, questa ‘anima’ ad unirsi allo ‘spirito universale’, il Brahman dopo innumerevoli reincarnazioni fino al completo esaurimento del ‘residuo karmico.’

Il corpo, e soprattutto il corpo dell’uomo, è importante, è lo strumento, l’unico, che può consentire all’atman il raggiungimento della moksha, la liberazione e l’interruzione definitiva del samsara, il ciclo delle rinascite. Non è dato a nessun altro essere vivente, solo l’essere umano può raggiungere la liberazione.

Gandhi diceva che il corpo è come l’arcolaio, pertanto va curato, manutenuto, riparato, oliato, utilizzato correttamente perché serva allo scopo, ma è solo uno strumento, niente più. Conseguentemente la morte riguarda solo il corpo, l’anima o, più correttamente, l’atman non muore, non può morire essendo ‘essere’ e l’ ‘essere’ non può ‘non essere.’ L’anima è innata, cioè ‘non nata’ in quanto sempre esistita e – così come tutto ciò che nasce muore – ciò che non nasce non può morire.

Nella Bhagavad Gita (II, 20) si legge: “L’anima che è dentro ogni uomo mai nasce né muore; non è stata, non sarà di nuovo. Essa che è innata, necessaria, eterna, primordiale, non muore quando muore il corpo”.

Per questo, pur nel dolore che la morte arreca tra gli uomini, essa è vista in India in un’ottica diversa da quella occidentale, è considerata come una nuova nascita.

Non si tratta infatti di un qualcosa che finisce, ma di un qualcosa che continua. Tant’è che la morte in India non è contrapposta alla vita bensì alla nascita e, come la nascita, non è altro che uno dei tanti passaggi da una condizione ad un’altra.

Significativamente l’utero materno è considerato come una tomba dove muore un determinato stato dell’essere per nascere in un altro e, correlativamente, la tomba è considerata come un utero dove si consuma la distruzione del corpo e da cui l’essere passerà ad una nuova condizione attraverso una nuova nascita.

La convinzione che “tu non sei il tuo corpo” ha come conseguenza che anche i riti funebri e il culto degli avi siano diversi da quelli occidentali.

La distruzione del corpo mediante la cremazione (metodo assolutamente maggioritario utilizzato in India per disfarsi del cadavere) e i riti conseguenti sono tutti volti a consentire all’atman di proseguire in modo corretto il percorso che ancora deve compiere.

Non esiste, non c’è motivo che esista, un corpo da venerare, una tomba su cui pregare e neppure un nome da ricordare, il defunto perde nome e forma (namarupam), esiste solo l’atman e i riti sono destinati a favorire il compimento del percorso che l’atman deve fare.

Il defunto perde i connotati della propria individualità tanto che assume un nome comune a tutti gli altri defunti. In genere si chiamerà Sarma se era di casta brahmana, Varma se kshatriya, Gupta se Vaisya e Dasa se Sudra e a lui sono dedicati i riti solo fino alla terza generazione. In pratica si celebrano i riti per il padre, il nonno e il bisnonno defunti. Quando morirà il figlio, per il bisnonno non verranno più celebrati riti e così via di seguito.